Four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie.

From “Sing a Song of Sixpence,” author uncertain

The rusty blackbird’s scientific name is Euphagus carolinus. The genus name, Euphagus (you-fa-gus), means “good to eat.” While few if any modern-day gourmands would contemplate working blackbirds into meals, such was not the case in the late 19th century. Barrels of songbirds were shipped to markets in large cities to be eaten.

Fortunately, wholesale slaughters of songbirds for food ended long ago, but plenty of other threats have arisen. The little-known (at least among non-birders) rusty blackbird epitomizes species that are apparently dying a slow death. Threats to the charismatic blackbird are both acute and quantifiable and seemingly vague and hard to define.

The morning of March 24 dawned clear and crisp, and Shauna Weyrauch, an Ohio State University researcher, and I headed to the vast wetlands of Killbuck Marsh Wildlife Area near Wooster. With cameras in hand and the temperature at 22 degrees, we set out into the marshes to photograph the scores of northern pintail and other ducks that were present. Killbuck encompasses nearly 6,000 acres and is an important waystation for migrant waterfowl.

Our trek took us through waterlogged swamp forests and marshes ringed by large stands of buttonbush. The plant is a shrub of saturated soils, often growing in standing water. It forms nearly impenetrable thickets and is important to many species of animals. Wood ducks feast on its fruit, green herons and night herons stalk amphibians in the tangles, and come summer, scores of pollinators visit buttonbush’s white flower clusters.

Buttonbush, a natural habitat

Buttonbush is also an invaluable habitat for migratory rusty blackbirds. As we passed by the buttonbush swamps, I began to hear the squeaky gurgles of rusty blackbirds. Most of the birds were deep in the plants, strutting among the wet leaf litter, flipping leaves to uncover macroinvertebrate animal life.

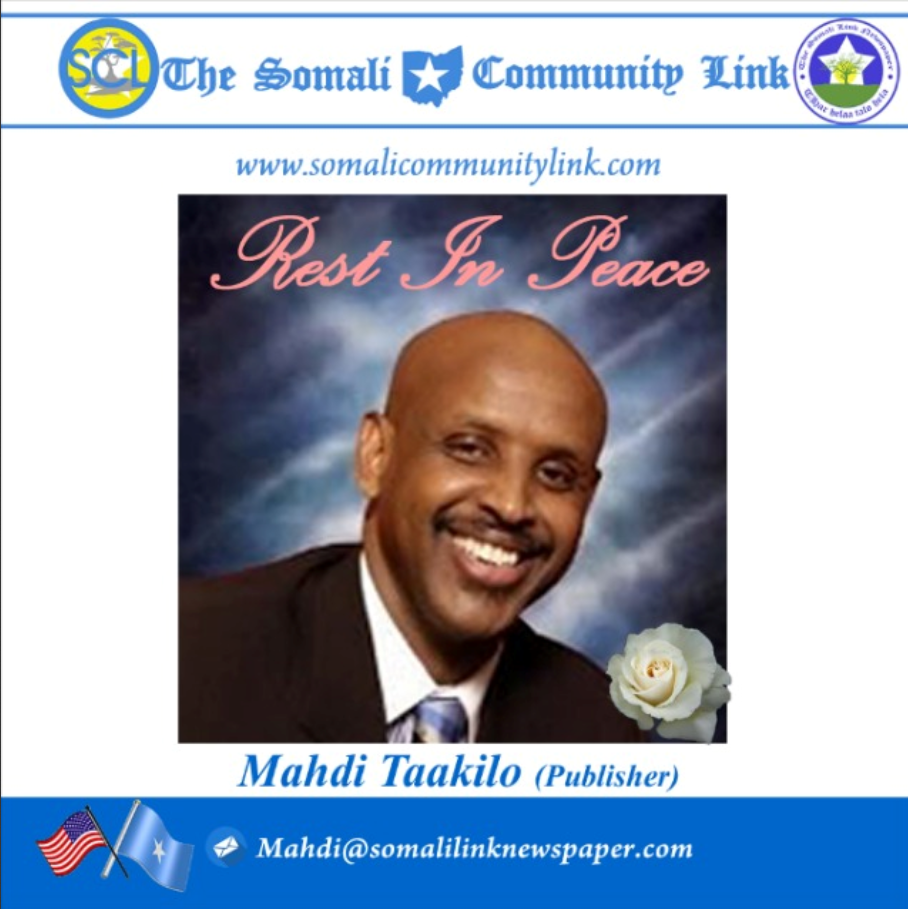

In all, we eventually estimated that about 300 rusty blackbirds were present — the largest flock that I’ve seen in many years. Occasionally, birds would perch in the open, such as the one in the accompanying photo. Males glare with bold yellow eyes and their plumage is an artistic montage of metallic blue and black with contrasting buffy feather edges. The female is a muted, ashy gray.

Most rusty blackbirds winter in the southern states, from Arkansas and Mississippi to the Atlantic coast, with small numbers sticking out in more northerly latitudes such as Ohio. The birds we saw were migrants from points south, and March sees the largest movement of northbound birds through this region.

Rusty blackbirds breed far to the north of Ohio, over the length and breadth of the boreal forest. They nest from Alaska to Newfoundland and north to the shores of Hudson Bay. This is the most northerly of North American blackbirds, and some birds probably travel 1,500 or more miles between breeding and wintering grounds. The Killbuck blackbirds still have a long way to go, chasing the tail end of winter northward.

Loss of habitat affects blackbirds

Once abundant throughout its range, the rusty blackbird has experienced a cataclysmic decline in recent decades. Some estimates peg the total population loss at 85–95%. Some of the contributing factors are clear-cut. Rusty blackbirds are dependent on wooded wetlands at all seasons, and wetland losses have been enormous in the bird’s migratory corridors and wintering grounds.

About 90% of Ohio’s wetlands have been drained or otherwise destroyed, and equally grim statistics apply in many other states. Logging of breeding habitats in the north has been shown to adversely affect breeding success, and the loss or decline of beavers in some regions has had negative impacts. The mammalian engineers create wonderful rusty blackbird nesting habitats in the backwaters of their dams.

Large-scale slaughter of wintering blackbird roosts, especially in southern states, to protect agricultural interests has certainly taken a toll on rusty blackbirds, even though they normally constitute a small percentage of such flocks.

More insidious is chemical contamination, especially by mercury. Over the past century and a half, human activities such as the production of electricity, mining, and waste incineration have more than doubled the natural levels of mercury in the environment. Mercury accumulates in wetland sediments — the foraging habitat for rusty blackbirds. In some regions, mercury levels in rusty blackbirds are the highest reported for any songbird species. Such toxicity has been shown to lead to poor reproductive success in birds.

The rusty blackbird is a bellwether of a degraded environment. It would be wise for us to pay attention to what this charismatic blackbird is telling us.