One evening last week, Stephen Miller, a policy adviser and central figure in the Trump White House, was lounging in the West Wing.

Miller, who has crafted speeches and policies for the president since his early days in office, is also one of the few members of the president’s initial team still with him at the end.

Leaning against a wall and chatting with colleagues about a meeting scheduled for later that day, he seemed in no hurry to leave.

The West Wing usually hums with activity but it seemed deserted. The phones were quiet. Desks in empty offices were cluttered with papers and unopened letters, as if people had left in a hurry and would not be coming back. Dozens of senior officials and aides quit in the wake of the Capitol riots on 6 January. A handful of loyalists, like Miller, remain.

As the conversation began to wind down, he broke away from his colleagues. When I asked him where he was headed next, he smiled. “Back to my office,” he said and sauntered down the hall.

On inauguration day, Miller’s office will have been cleaned out, swept of signs that he and his colleagues had ever been there, ready for the Biden team to move in.

The cleaning out of West Wing offices, and the transition between presidents, is part of a tradition that dates back centuries. It’s a process that has not always been imbued with warmth.

Another impeached president, Andrew Johnson, a Democrat, snubbed Republican Ulysses S Grant in 1869 and skipped the inauguration. Grant, who had backed Johnson’s removal from office, was hardly surprised.

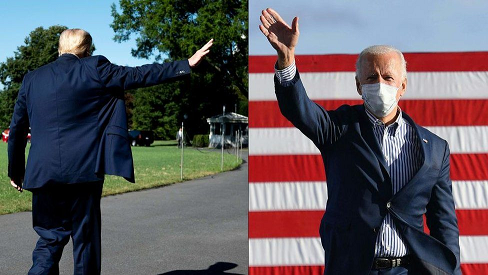

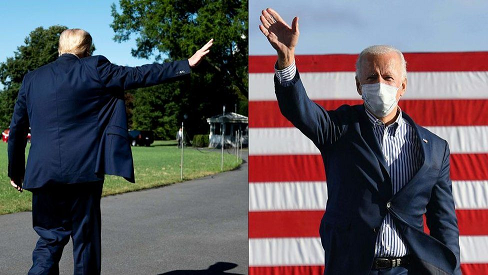

This year, however, the transition stands out for its acrimony. The process usually starts straight after the election, but it started weeks late after Trump refused to accept the result. And the president has said he will not attend the inauguration. Most likely, he will instead travel to his Mar-a-Lago club in Florida.

Still, the handover is taking place, just as it has in the past. “The system is holding,” says Sean Wilentz, a professor of American history at Princeton University. “It’s very rocky, it’s very bumpy, but nevertheless the transition is going to occur.”

Even in the best of times, the logistics of a transition are daunting, involving the transfer of knowledge and employees on a massive scale.

Stephen Miller is just one of 4,000 political appointees hired by the Trump administration who will lose their job and be replaced by individuals hired by Mr Biden.

During an average transition, between 150,000-300,000 people apply for these jobs, according to the Center for Presidential Transition, a nonpartisan organisation based in Washington. About 1,100 of the positions also require Senate confirmation. Filling all of these positions takes months, even years.

Four years of policy papers, briefing books and artefacts relating to the president’s work will be carted off to the National Archives where they will be kept secret for 12 years, unless the president himself decides that portions may be released early.