Germany is following in the footsteps of France and Austria, with increasingly oppressive proposals to target Muslim communities.

spectre is haunting Europe: the spectre of political Islam. From France’s fight against “Islamo-leftism” to Austria’s battle against “political Islam”, Muslims and Muslim anti-racist civil society groups are coming under more and more pressure from state authorities.

In both countries, governments have shut down NGOs and mosques, limited freedom of expression, and raided homes and institutions under the pretext of the “war on terror”. Such measures intensified after terrorist attacks were carried out last year.

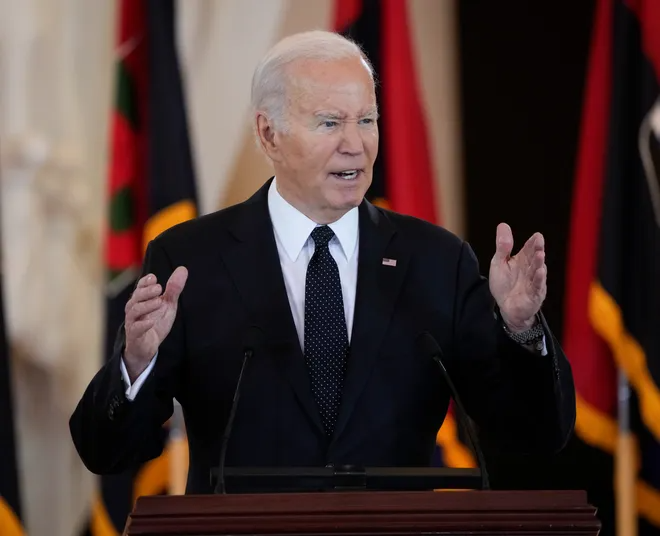

In Germany, Chancellor Angela Merkel’s Christian Democratic Union (CDU) appears set to follow in the footsteps of French President Emmanuel Macron and Austrian Chancellor Sebastian Kurz. While Macron was met with harsh international criticism for his anti-Muslim legislation, Kurz’s initiatives went nearly unnoticed. But they all seem to follow the same playbook, claiming to protect the majority of peaceful and law-abiding Muslims while targeting only the “dangerous” Muslims.

In reality, they are dramatically widening the group of potentially “dangerous Muslims”.

According to a recent publication by the CDU/CSU alliance in the German parliament: “Islamism is not confined to a certain number of violent menaces. The ideology behind it is poison for our liberal society. It endangers integration and social cohesion by inciting Muslims against our democracy.”

This crusader rhetoric does not come out of thin air. Statements like these build on a long and problematic history of “countering violent extremism” and “deradicalization programme”, which emerged after the “war on terror” was initiated two decades ago.

State surveillance

A more recent development has been the broadening of the notion of “countering violent extremism” to include the targeting of “non-violent extremism”. The latter term implies that non-violent Muslim groups share the same goals as violent ones, and differ only in methodology, as noted in a Bavarian intelligence report.

This term is used to exclude Muslim organisations from civil society by targeting Muslim associations that work within the western democratic political order and reject violence. According to the report, these legal, non-violent means include operating “cultural associations and mosques, which serve to recruit members on the one hand and to spread their ideology on the other hand. Through their umbrella organisations, they try to offer themselves to the state as the mouthpiece of Muslims.”

This concept targets mainstream Muslim groups, rather than subversive movements hiding in the shadows. Most mainstream Muslim associations have been subjected to state surveillance for years in Germany. A general suspicion underlies this discourse, treating Muslims with mistrust and cynically questioning their integrity.

The term being applied broadly is “political Islam”, but not in the way academics would use it to differentiate between diverse manifestations of the intersection of politics and religion. The problem with the vague term “political Islam” in countries such as Austria is that the government uses it to criminalise Muslim practices and to silence Muslims who express political opinions critical of the government.

In a sense, it has become the intellectual foundation upon which to institutionalize a general demonization of Muslims, reminiscent of Joseph McCarthy’s witch hunt in the 1950s against Black and leftist groups under the banner of anti-communism.

Hardline positions

The growing hardline positions of European countries such as Austria, France and Germany seem to be coming in tandem. Last October, a group of well-known authors and politicians from Germany’s CDU/CSU signed an open letter that proposed five recommendations for “strengthening the free democratic basic order in the face of political Islam”. The letter noted: “It is high time to face the problems of the immigrant society openly and not to be intimidated by unfounded accusations of alleged Islamophobia.”

Similar to France’s culture war against gender, postcolonial and racism studies, these scholars were trying to immunize the status quo against any critique.

Did this letter gain traction because of the attacks in France and Austria last year? Not really, for the claim is that “political Islam” is much more dangerous than militant violence stemming from Muslims.

The five recommendations include establishing a “documentation centre” based on the Austrian model, in which “the structures, strategies and financing of political Islam are analysed and disclosed”; the establishment of 10 university chairs dedicated to analysing the structures of “political Islam” in Germany; and the establishment of an expert group within the interior ministry to make recommendations in the fight against political Islam.

Such ideas raise serious questions. Austria’s Documentation Centre is largely run by hawkish law-and-order figures who have a long history of supporting anti-Muslim legislation, including people like Mouhanad Khorchide, Susanne Schroter and Lorenzo Vidino.

The recent CDU/CSU position paper also argues that state authorities should stop supporting associations that fall under the category of “political Islam”, and proposes creating a “German imam”, designed to be a Germany-trained student who is attached first and foremost to German national identity and thus reproduces the existing power structures. The paper also calls for stricter financial controls on Muslim groups.

The goal is to surveil Muslims as much as possible, violating secular notions of separating state powers and religious communities. As similar measures have not been enacted against other religious communities, it seems that Muslims are being singled out as targets yet again.

The views expressed in this article belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect the editorial policy of Middle East Eye.