Civilians caught up in Sudan’s civil war have given graphic accounts to the BBC of rape, ethnic violence and street executions. Our journalists have managed to make it to the front line of the fighting close to the capital, Khartoum.

Top UN officials have said the conflict has plunged the country into “one of the worst humanitarian nightmares in recent history” and could trigger the world’s largest hunger crisis.

There are also fears that in Darfur, in the west of the country, a repeat of what the US called genocide 20 years ago may be beginning to unfold.

As if out of nowhere, a huge blast shakes the road in Omdurman. People scream and run in all directions, shouting: “Go back, go back, there’ll be another one.” Thick smoke blankets everything.

Moments earlier, the battered street had been dotted with pedestrians picking up rice, bread and vegetables from the shops, which had only recently begun to re-open.

In mid-February, the Sudanese army retook the city – one of three along the River Nile that form Sudan’s wider capital, Khartoum.

Civilians have now started to return, but mortars, like the one that landed in the middle of this main street, still fall daily.

For international media, gaining access to cover the civil war that erupted last April has been difficult – but the BBC has managed to get to the front line.

Our team found the once-bustling heart of Omdurman transformed into a thinly inhabited wasteland.

The vicious power struggle between the country’s military and its former ally, the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) paramilitary group, has killed at least 14,000 people across the country – possibly many more.

For nearly a year, the army and the RSF have battled over Khartoum and the nearby cities.

The RSF has taken control of areas south of the capital, as well as large swathes of Darfur, which has been in turmoil for years with violence between its various African and Arab communities.

Women who escaped Darfur to neighbouring Chad have given the BBC accounts of being raped – sometimes multiple times – by militiamen. Men in the camps told us they had escaped street executions and abductions.

Embedded on the front line with the army in Omdurman, the BBC team’s movements were carefully controlled – we had a minder with us and were not allowed to film military activity.

The army fears information about its activities will be leaked.

When our cameraman begins filming the aftermath of the mortar explosion, armed men in civilian clothing surround him, one pointing a gun at his head.

They turn out to be from military intelligence, but it’s a sign of how high tensions are.

Despite the army’s recent gain in Omdurman, we can still hear exchanges of fire crackling around the area from time to time.

Part of the front line now runs along the Nile, which separates Khartoum on the eastern side from Omdurman, which is west of the river.

The military tell us RSF snipers are stationed in apartment blocks across the water from Sudanese army positions at the badly damaged parliament building.

Omdurman’s old market, once busy with locals and visitors, is in ruins, its shops looted bare. Most vehicles on the roads are military.

More than three million people have fled Khartoum State in the past 11 months, but some Omdurman residents have refused to leave. Most we meet are elderly.

Dany Abi Khalil / BBC”It’s just me left,” says Mukhtar al-Badri Mohieddin, listing friends and acquaintances who are now buried

Dany Abi Khalil / BBC”It’s just me left,” says Mukhtar al-Badri Mohieddin, listing friends and acquaintances who are now buried

Less than a kilometre from the front line, Mukhtar al-Badri Mohieddin is walking with a stick near a mosque with a damaged minaret.

The open space opposite is covered with makeshift graves – rough earth mounds marked with broken bricks, boards and concrete slabs.

“There are 150 people here. I knew many of them, Mohamed, Abdullah… Jalal,” he says, pausing for a long moment before one name, Dr Youssef al-Habr, a well-known professor of Arabic literature.

“It’s just me left,” he adds.

The Sudanese military has been criticised for its heavy use of aerial bombing, including in civilian areas where RSF fighters hide out – though it says it takes “necessary precautions” to protect civilians.

People here hold both sides responsible for the destruction in and around the capital.

But many accuse the RSF of looting and attacks during the time it controlled the area.

“They cleared the houses of belongings, they stole cars, TVs, they beat up old people, even women,” resident Muhammad Abdel Muttalib tells us.

“People died of hunger, I pulled some of them out of their houses so the bodies wouldn’t rot inside,” he adds.

He says it is “widely known” that women were raped in their homes and groped during security checks.

Afaf Muhammad Salem, in her late fifties, was living with her brothers in Khartoum when the war broke out.

She says she moved across the river to Omdurman after they were attacked by RSF fighters, who she says looted their house and shot her brother in the leg.

“They were beating up women and old men and threatening innocent girls,” she says.

It is a veiled reference to sexual violence, which is a taboo topic in Sudan.

“Insulting honour does more harm than taking money,” she adds.

‘A weapon of revenge’

Victims of rape can face a lifetime of stigma and marginalisation from their own families and communities. Many people in Omdurman did not want to discuss the issue.

But more than 1,000km (621 miles) to the west, in the sprawling refugee camps over the border in Chad, the volume of emerging testimonies of sexual violence is forcing a new, grim, level of openness.

Marek Polaszewski / Hundreds of thousands of people have fled from Sudan into Chad

Marek Polaszewski / Hundreds of thousands of people have fled from Sudan into Chad

Amina, whose name we have changed to protect her identity, has come to a temporary clinic run by the charity Médecins Sans Frontières, seeking an abortion. She greets us without looking up.

The 19-year-old, who has fled from Darfur in Sudan, only found out she was pregnant the previous day. She desperately hopes her family will never know.

“I’m not married and I was a virgin,” Amina says in faltering sentences.

- If you have been affected by any of the issues raised in this story you can visit BBC Action Line.

In November, militiamen caught her, along with her aunt and cousins, as they were fleeing from their hometown of Ardamata to the nearby city of Geneina, she tells us.

“The others escaped but they kept me for a whole day. There were two of them, and one raped me many times before I managed to escape,” she says.

Marek Polaszewski /Amina desperately hopes her family will never know she sought an abortion

Marek Polaszewski /Amina desperately hopes her family will never know she sought an abortion

The RSF’s expanding domination in Darfur, supported by allied Arab militias, has brought with it a surge in ethnically driven attacks on the black African population, especially the Masalit ethnic group.

Amina’s story is just one of many testimonies of attacks against civilians that happened around 4 November when the RSF and its allies seized a Sudanese military garrison in Ardamata.

It follows violence earlier in the year – a recent UN report seen by the BBC says that more than 10,000 people are believed to have been killed in the area since last April.

The UN has documented about 120 victims of conflict-related sexual violence across the country, which it says is “a vast under-representation of the reality”.

It says men in RSF uniform and armed men affiliated with the group were reported to be responsible for more than 80% of the attacks. Separately, there have also been some reports of sexual assaults by the Sudanese military.

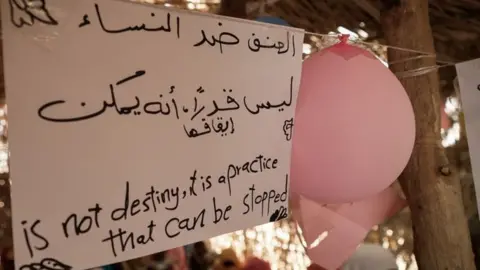

Just outside the same camp, which is in the border town of Adré, about 30 women and girls meet in a hut at midday.

Pink and blue balloons hang from a string above their heads, along with handwritten notes. “Rape is not destiny; it is a practice that can be stopped,” one reads.

Tears flow freely as the women speak of their experiences of both physical and sexual violence.

Marek Polaszewski /Women wept in the meeting as experiences of physical and sexual violence were shared

Marek Polaszewski /Women wept in the meeting as experiences of physical and sexual violence were shared

Maryamu – not her real name – says she was raped by armed men wearing the turban-style headdresses typical of Arab fighters in the area, in November in her home in Geneina.

She had difficulty walking afterwards, she says, sobbing as she describes fleeing: “People were running, but we couldn’t because my grandmother can’t run. I was also bleeding.”

Zahra Khamis, a social worker who is a refugee herself, runs the group.

Both Amina and Maryamu are from black African communities, and Ms Khamis says these, particularly the Masalit ethnic group, are being targeted in Darfur.

Marek Polaszewski / Balloons and handwritten signs hang in the hut where women gather to share their experiences

Marek Polaszewski / Balloons and handwritten signs hang in the hut where women gather to share their experiences

During the war in Darfur 20 years ago, an Arab militia called the Janjaweed – in which the RSF has its roots – was mobilised by former President Omar al-Bashir to crush a rebellion by non-Arab ethnic groups.

The UN says 300,000 people were killed and rape was widely used as a way to terrorise black African communities and force them to flee. Some Janjaweed leaders and Mr Bashir have been indicted by the ICC on charges of genocide and crimes against humanity. They have denied the charges and no-one has been convicted.

Ms Khamis believes rape is being used in this conflict “as a weapon of revenge”.

“They are doing this to the women because rape leaves an impact on society and the family,” she adds.